A Skype interview with Kelsey Fraser, who will be showing work at Text Crutch, curated by Robert Harpin. The show will run from October 26 - November 2, 2013 at The Works Gallery at Jackson Power (9744 60 Ave). The opening reception will be held on October 25th, 7 - 10pm.

What are your influences?

I am influenced by awkward moments, both moments I’ve had personally and moments I’ve witnessed—like the quirks of humanity, the quirks of each individual. And I’m influenced by country music lyrics. As far as artists go, I’m influenced by Ian Stevenson, Mira Calman, and David Shrigley.

I don’t know if they approach it that way, but I view [their work] as a very child-like sense of exploration. They all have an innocent way of viewing the world, which is often times very funny—commenting on our insecurities in a way that’s amusing.

How do you incorporate text into your work?

It’s kind of a new thing for me. In my last year at ACAD I started using text in my work and I was hesitant to begin using it because I was unsure how text would influence how a viewer viewed my work. I guess I use it very sparingly. By just giving a little hint to the viewer or a little sentence that they can then read in their mind or out loud—however they choose to view the work. They kind of become part of the work through their own inner monologue, I guess.

Many of your works are really funny. How do you use text for comedic effect?

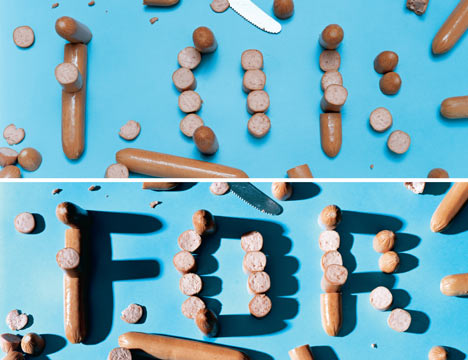

Again, I go back to the notion of childhood with ideas of play and exploration with language. Some words are really funny, just on their own or if you break them up or if you space them slightly differently or play them back-and-forth with an image. I really love creating little sentences or declarations in my work that I feel the viewer will then become implicated in—whether they want to be or not—by basically reading what I’ve written. It kind of puts them into this situation—whether they want to be there or not… my work [tries] to incorporate the inner voice of the viewer.

I don’t’ really know how it’s viewed, but whether you write something large or small or the font you use it creates its own little character. And it can be more child-like or more aggressive or meek in how you write something. For me, when it comes to that, I might not consciously think about the style I’m writing in. But I do consciously think about how large or small I write something, depending how I want it to be viewed. I guess it’s more about the spacing, for me. And how it’s situated in the room, where it is on the wall, and if there’s a conversation happening between different text pieces. When I view other text-based work, sometimes I do think about how the actual word was written and imagine myself writing that word.

I did a piece once where I filmed myself writing. I just had a camera in one hand, and I was writing with the other hand. And it was really not very well filmed, obviously—in an out of focus because it was on autofocus. And I didn’t realize really what I was doing at the time. But it became very funny, after looking back at it to see where I would pause. I would pause when I didn’t know how to spell a word. That was pretty humorous because I don’t know how to spell many words. Or if you choose to punctuate something or how hard you choose to press down on the paper can really bring home a point.

[I used the video] for a presentation in my fourth year, where we had to give an artist talk. I introduced different subjects with the video… I would like to come back to that. It kind of overshadowed everything else I did in my artist talk. These short video clips took on a funny life of their own. They became a piece of their own.

How do you interpret the title Text Crutch?

As far as using text as a crutch in your work—that’s cool if you do. It’s all up to the viewer to interpret it. If you need words to help your work along—like a little pick-me-up—then go for it! I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. I guess I enjoy work that takes a little bit more to decipher. I guess I like to invest a little more time in it, and if I feel like it’s just one-dimensional, I’ll move on quicker. I don’t know if I’ve experienced much art that’s used text in that way. Usually I find text adds another element to the work. Just another layer.

Kelsey Fraser has a BFA in Drawing from the Alberta College of Art and Design.

This interview is brought to you by TickTalk at The Works.